Back to Blogs

Discover

Abbey Treasures

From Cambridge to Rome, we go in search of the surviving treasures from the Abbey of St Edmund.

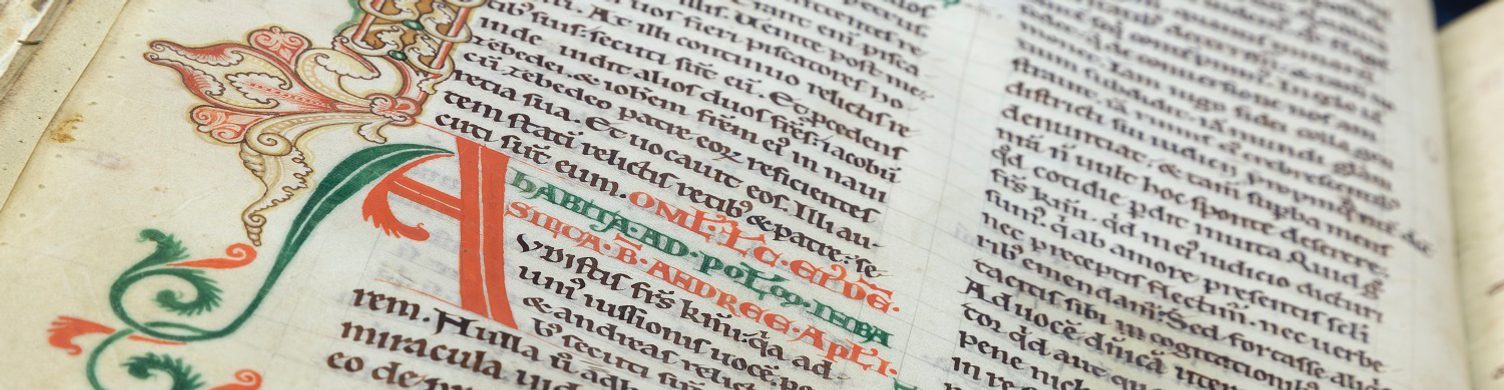

The Bury Bible

The Bury Bible is a giant illustrated Bible written at Bury St Edmunds between 1121 and 1148, and illuminated by an artist known as Master Hugo, the earliest recorded professional artist in England. He was in residence at the Abbey of St Edmund from before 1136 to after 1148.

Since 1575, The Bury Bible has been in the Parker Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. It is the only surviving volume of a large two-volume bible produced for the monks of the Abbey of St Edmund.

It is an important example of Romanesque illumination from Norman England, and bears comparison with other giant bibles produced in England in the 12th century such as the Dover Bible (also in the Parker Library), Lambeth Bible, Rochester Bible, and the Winchester Bible.

It is not known where Master Hugo was born or trained. According to the Fitzwilliam Museum, “the magnificent colour patterns of his paintings, the startlingly new Byzantine draperies and the deep-staring eyes of Moses, Aaron and the Jews suggest that he had travelled at least to southern Italy and probably also to Cyprus, Byzantium, and even the Holy Land.”

After the dissolution of the abbey of Bury St Edmunds at the Reformation the Bible eventually came into the hands of Matthew Parker. Parker was a powerful figure of the English Reformation who was largely responsible for the Church of England as a national institution. Parker's talents were sought by both Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. He served as chaplain to Anne Boleyn and proved himself a capable administrator, becoming Master of Corpus Christi College (1544-53), Vice-Chancellor of Cambridge University, and Archbishop of Canterbury (1559-75).

Parker was an avid book collector, salvaging medieval manuscripts dispersed at the dissolution of the monasteries; he was particularly keen to preserve materials relating to Anglo-Saxon England. The extraordinary collection of documents that resulted from his efforts is still housed at Corpus Christi College, and consists of items spanning from the sixth-century Gospels of St. Augustine to sixteenth-century records relating to the English Reformation.

You can view the Bury Bible online at Stanford Libraries website.

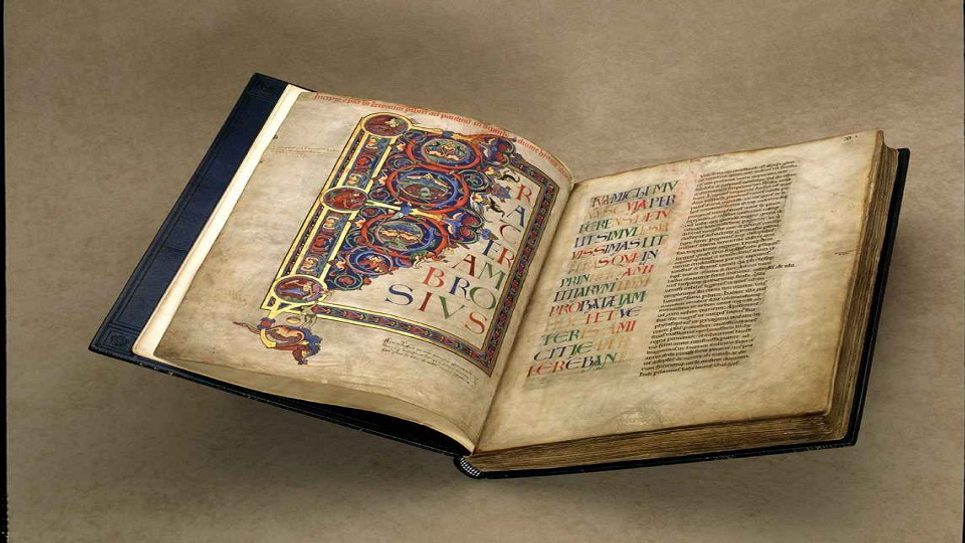

Pembroke Manuscripts

Eighty manuscripts from the library of the Abbey of St Edmund were given to Pembroke College in Cambridge by a man named William Smart in 1599. Smart’s gift represents the most intact monastic library surviving in Britain.

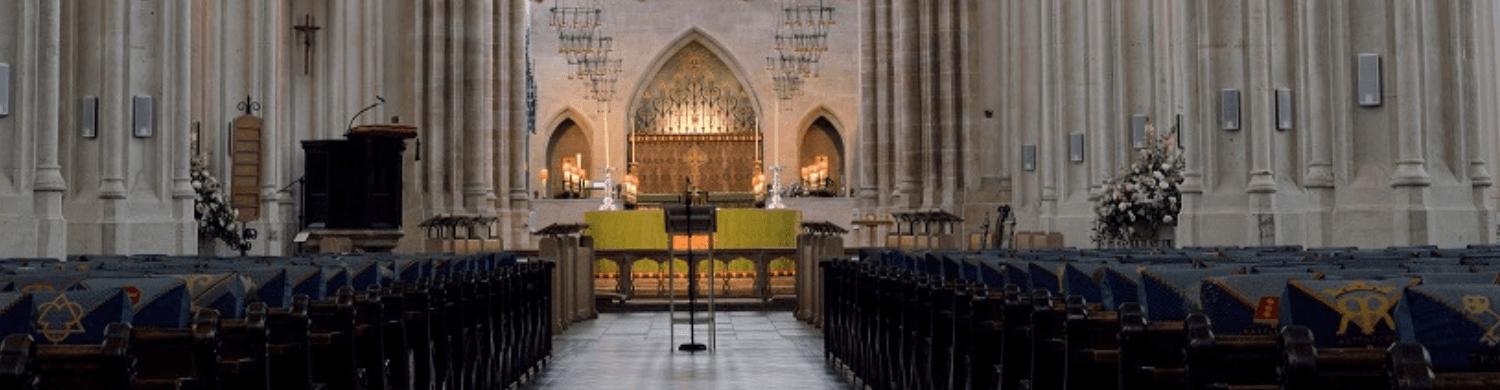

Hand written and decorated by monks in the Abbey, seven of the manuscripts from the Abbey Scriptorium were reunited for the first time in their place of origin since 1539 at St Edmundsbury Cathedral as part of the Abbey’s 1000th anniversary celebrations in 2022.

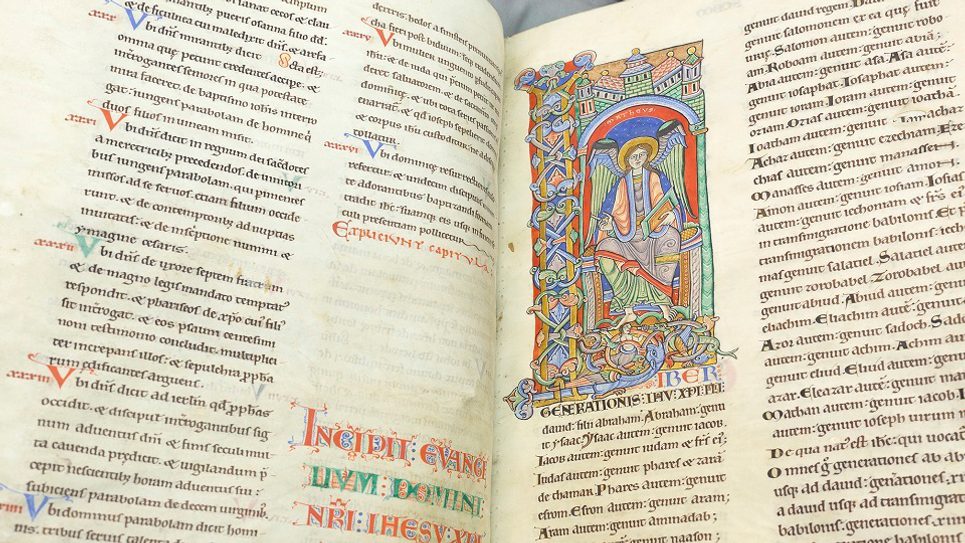

Bury St Edmunds Psalter

The Bury Psalter, which contains the earliest textual evidence for the Abbey from about 1050 remains in one of the most secure buildings in the world, the Vatican Library.

The Bury St Edmunds Psalter is a famously beautiful copy of the Psalms with marginal line-drawings.

Containing state papers, correspondence, account books, and many other documents that the church has accrued over the centuries, the Vatican Library and Archives has been cloaked in mystery for years but many of the documents the library holds can now be seen online. See the Bury St Edmunds Psalter online at the Vatican Library website.

A later Bury Psalter (1398 and 1415) is looked after by Suffolk Archives in Bury St Edmunds and sometimes goes on display at special events.

The Bury Psalter was written at the Benedictine Abbey of St Edmund, probably between 1398 and 1415, and is a wonderful example of an English monastic service book. The Psalter was presented to the King Edward VI School by James Hervey in 1706, having once belonged to his grandfather, James Cobbs, who owned a number of manuscripts from the Abbey of St Edmunds in his private collection.

The Bury Psalter comprises a Calendar, the Psalms of David, Canticles, Litany and Preces, Placebo and Direge (Offices of the Dead), Canticles for Christmas and other festivals and a Hymnarium with musical notation.

Medieval Psalters, comprising 150 Psalms, were often divided into ten sections for daily recitation, with historiated initials and additional decorative treatment marking the main divisions at Psalms 1, 26, 38, 51, 52, 68, 80, 97, 101 and 109. This is exactly the case with our Bury St Edmunds Psalter. The texts are framed by partial bar borders on flourished grounds of various rich colours contrasted with lavish gold.

Video: Suffolk Archives

The Bury Cross or Cloisters Cross

The replica of the Bury St Edmunds or Clositers Cross can be seen at St Edmundsbury Cathedral. Photo: Rebecca Austin

On display at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Bury Cross or Cloisters Cross, as it is now known, is made from walrus ivory and believed to be from the Abbey of St Edmund in Bury St Edmunds. It was discovered in a Zurich bank vault at the end of World War II.

The sculptor is not known but it is believed to have been created from around 1150-1160. Thomas Hoving, who managed the acquisition of the cross while he was associate curator at The Cloisters, concluded that it was carved by Master Hugo, the earliest recorded professional artist in England who was in residence at the Abbey from before 1136 to after 1148. A replica, made by The Metropolitan Museum's Ron Street in 2004 from epoxy resin, is on display in The Treasury at St Edmundsbury Cathedral in Bury St Edmunds.

The history of the cross before it was acquired by the Croatian art collector Ante Topić Mimara (1898–1987) is unknown. He sold it to the Metropolitan Museum in 1963. The British Museum was also keen to buy the cross, but they eventually declined, because Topić Mimara steadfastly refused to provide proof that he had full title to sell the cross. Hoving reportedly sat up drinking coffee with Topić Mimara until after midnight on the night that the British Museum's option lapsed, and he purchased the cross immediately afterwards for £200,000.

On this intricately carved cross, believed to have been created around 1150 and 1160, 92 figures and 98 inscriptions present a number of biblical scenes.

However, there is debate over whether or not the inscriptions were chosen with an anti-Semitic intent. On the Museum’s website it says: “among the Latin inscriptions are several insidious invectives against Jews, a sobering testament to the pernicious presence of anti-Jewish sentiment in medieval Europe. While the words on this particular cross would have been known only to a community of English churchmen, such hateful attitudes permeated society and led to waves of unconscionable persecution of Jews, from London to York. In Bury Saint Edmunds, the Suffolk town with which this cross has often been associated, scores of Jewish residents were killed, and the survivors expelled in 1189, about the time this cross was carved. A century later, in 1290, Edward I expelled all Jews from England.”

You can see the Cloisters Cross at the Met Museum website. The replica can be seen at St Edmundsbury Cathedral's Treasury.

The Edmund Jewel

The Edmund Jewel on display at Moyse's Hall Museum. Photo: Sue Warren

At Moyse's Hall Museum you can see an extremely rare piece of jewellery with possible links to St Edmund himself.

The ornate gold jewel, known as the 'Edmund Jewel' may have even been used by the great king himself and was discovered by someone metal detecting in a field in Drinkstone in 2014.

It is believed to be an aestal, a 9th century pointer used by people in high status for reading at a time when the majority of people were illiterate. Aestals themselves are believed to be extremely rare – there are thought to be less than 10 in Europe.

The Edmund Jewel dates back to the ninth century, Edmund was martyred in 869AD, so its unknown whether the jewel was made before or after his death.

It was found where what would have been part of the landholdings of the Abbey of St Edmund; land that some academics have suggested originally had connections to the King himself, while the rarity of the Jewel, coupled with its purpose means it is likely that, if it did not belong to Edmund himself, it would have been made and used by someone in high status in the Church.

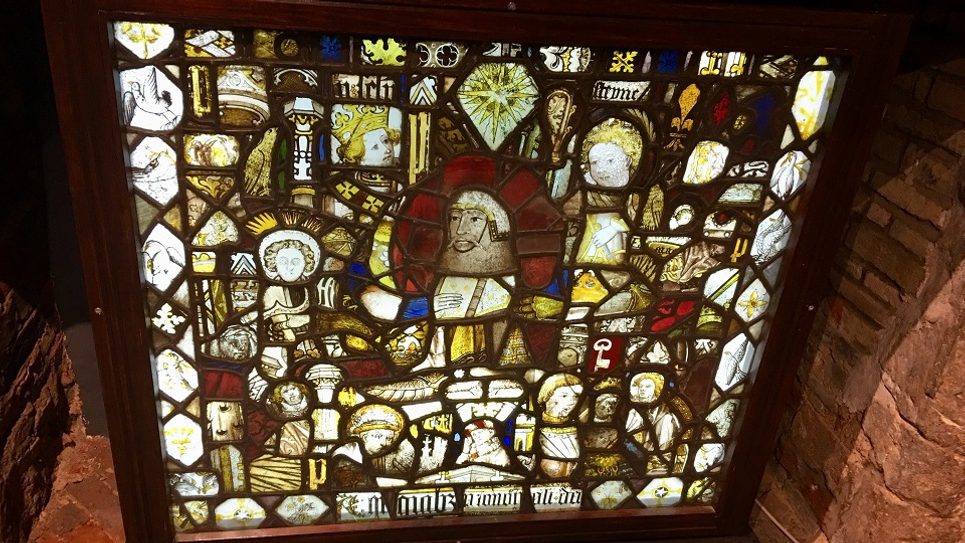

Abbey Glass

Stained glass on display at Moyse's Hall Museum

The Abbey Church at Bury St Edmunds would have been glazed with vast quantities of stained glass and you can see some of this today.

You can see some of the original stained glass from the Abbey of St Edmund at Moyse’s Hall Museum.

A wonderful mosaic, which contains stained glass from the original Abbey, is displayed on the ground floor of the museum which has been beautifully restored and back lit. A real piece of the Abbey's history and a colourful delight!

All Saints’ Church in Brandeston in Suffolk is believed to have glass from the Abbey of Bury St Edmunds itself – and, specifically, from the Abbey’s Chapter House. The Chapter House was where the monks gathered to make important decisions, and also hosted Parliament on several occasions.

In 1950 Christopher Woodforde reported that there was, or had been, a series of fragmentary depictions of Bury’s abbots in the glass at Brandeston, including Abbots William Curteys (ruled 1429–46), Thomas Rattlesden (ruled 1479–97) and William Bunting (ruled 1497–1513). Only one depiction of an abbot now survives, along with a single tonsured monk. Both the style of the glass and the survival of a fragment featuring the pomegranate badge of Queen Catherine of Aragon confirm that the glass set in a window on the south side of the nave dates from the reign of Henry VIII, and therefore from the very last years of St Edmunds Abbey when Bury was ruled by Abbot John Reeve.

Explore more on the lost glass of the Abbey in Martin Harrison and Dr Francis Young’s blog Mystery of the Lost Stained Glass.

The Douai Reliquary

Douai Abbey Reliquary

It is not every day that a lost treasure of the great Abbey of Bury St Edmunds comes to light!

An article by Marian Campbell and Michaela Zöschg in Burlington magazine features a recently discovered fourteenth-century reliquary that can be plausibly attributed to St Edmunds Abbey owing to the unusual choice of saints and the decorative scheme adopted.

In a blog by Historian Dr Francis Young, he says: "The figure of the crucified Christ is represented against fields of blue and red covered with gold crowns, which recalls the arms of St Edmunds Abbey and the See of Ely. The presence of a relic of ‘St Robert, martyr’ among the relics that line the edge of the reliquary strongly suggests a Bury provenance, since the antisemitic pseudo-saint Robert of Bury St Edmunds (supposedly killed by the town’s Jews in 1181) was venerated exclusively in Bury and had his own chapel in the Abbey’s crypt. The reliquary was discovered by Abbot Geoffrey Scott in the collections of Douai Abbey, the symbolic successor monastery of Bury St Edmunds founded in Paris in 1615 and now located at Woolhampton, Berkshire."

Dr Francis Young has written an article on this exciting new discovery.

Related Blogs

News

Abbey Project Awarded…

The project aims to conserve and protect the ruins;…

News

Cycle the Wolf Way

Winding its way around many of the best bridleways,…

News

360° Degree Vikings

The Brecks Fen Edge and Rivers Landscape Partnership…

News

Dame Barbara Woodward DCMG…

Dame Barbara Woodward DCMG OBE Announced as Speaker at…

News

Celebrate St Edmund's Day on…

St Edmund's Day is celebrated around the world every…

Latest news

News

Discover Suffolk's County Flower - the Oxlip

Did you know that Suffolk has a county flower? The Oxlip only grows in some woodland areas of Suffolk, Cambridgeshire and Essex.

News

Quentin Blake ‘The Illustrated Hospital’ exhibition at Bury St Edmunds Museum

A summer exhibition of illustrations by Quentin Blake at Moyse’s Hall Museum, Bury St Edmunds presents a rare opportunity to view a large collection of pieces by one of the nation’s favourite artists.

News

Abbey Project Awarded National Lottery Heritage Fund Grant

The project aims to conserve and protect the ruins; build a visitor centre, west cloister, and network of footpaths; and use digital technology to provide exciting interpretation for all ages and…

News

Walks at Rougham

Rougham Estate offers 18 miles of public footpaths, cycling routes and permissive pathways for you to enjoy.

News

Bury St Edmunds Celebrates English Tourism Week

Bury St Edmunds MP, Jo Churchill, met representatives from the town’s attractions and tour guides involved with the town’s Masters of the Air tourism campaign at Bury St Edmunds Guildhall.

News

Tours Take Off for Masters of The Air

Tours developed by Bury St Edmunds Tour Guides and Bury St Edmunds Guildhall to tie in with the Apple TV Series Masters of The Air so popular more dates are being added.

News

International illustrator David Hughes draws largest exhibition Bury St Edmunds

The largest ever exhibition is now underway at Moyse’s Hall Museum featuring the work of internationally acclaimed illustrator David Hughes.

News

A Taste of Bury St Edmunds and Suffolk

After visiting Suffolk's foodie capital, you'll want to take it with you - here are 5 foodie treats to take home!

News

Doctor Who Stars Coming to Bury St Edmunds to Star in Sherlock Holmes Classic

Who stars Colin Baker, Terry Molloy, and Rosie Baker will star in Hound of The Baskervilles at Bury St Edmunds Theatre Royal